5 Important Types of Contracts for Engineering Firms

The engineering contract is the foundation of every successful project. Learn about the types of contracts along with the pros and cons of each.

The architectural contract is the foundation of every successful building project; learn about the types of contracts and key terms to understand.

When your firm has a well-written architectural contract, you're able to access clear communication, understanding, and mutual respect between you and your clients. The way you write your contract can be the difference between a smooth project and a mass amount of misunderstandings, unnecessary costs, delays in the design development, and legal disputes. As a busy architecture firm, you know how important it is for everything in the project to run as smoothly as possible. Well by starting with a strong architectural contract, you can make this a reality.

You more than likely know what an architectural contract is, but how exactly do you write a 'bulletproof' architectural contract? You see, a bulletproof architectural contract is comprehensive, detailed, and addresses potential challenges that may arise during a project. It's the basic foundation of your project.

In this article, we'll discuss the key aspects you need to help you craft a bulletproof architectural contract. This will ensure a smoother project lifecycle and minimizing potential issues along the way.

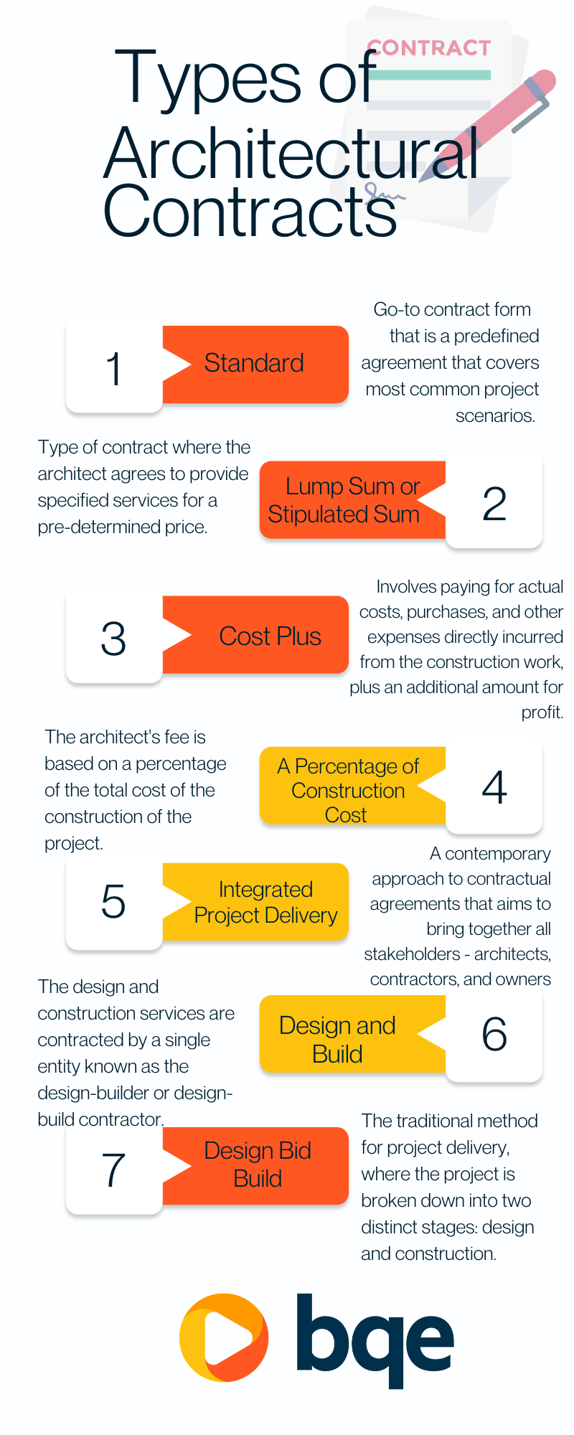

Let's start with the most basic architectural contract. The one you may be the most familiar with.

A Standard Architect Agreement or contract, is often based on templates provided by professional bodies like the American Institute of Architects (AIA). This serves as a go-to contract form for many of your architectural projects. It’s essentially a predefined agreement that covers your most common project scenarios and is designed to be fair and balanced to all parties involved.

This standard form contract usually includes important and common details such as the scope of work, schedule, fees and payment terms, dispute resolution methods, termination conditions, and insurance requirements, among other things.

The Standard Architectural contract is best for many standard or typical architectural projects where the project scope, schedule, and other professional services key elements are relatively straightforward and adhere to common architecture and construction industry practices.

It's also an excellent starting point for new architects or clients unfamiliar with the process, as it covers the essential elements in an accessible format, although customization might still be required to suit the project's specifics.

A Lump Sum or Stipulated Sum contract refers to a type of contract where you, the architect, agrees to provide specified services for a pre-determined price. The architect will carefully estimate the cost of the entire project and provide a single 'lump sum' price.

The advantage of this contract is its simplicity and certainty: the client knows exactly what they'll pay for the project, fostering budgetary confidence.

This contract is typically used when the project scope is clearly defined, and the schedule is well-detailed, leaving little room for unexpected revisions or variations.

For this type of contract to operate effectively, it's important that the contractor furnishes cost estimates that are as precise and exhaustive as possible.

Now let's discuss the Cost Plus contract.

A Cost Plus contract involves paying you for actual costs, purchases, and other expenses directly incurred from the construction work, plus an additional amount for profit. The extra amount may be a fixed sum or even a percentage of the total costs.

Now the main advantage of a Cost Plus Contract is it brings you flexibility – it allows adjustments to the project scope and design without having to renegotiate the entire contract. This is great for if you need some extra time savings.

A Cost Plus contract is most typically used when the scope of the project isn't fully defined at the very beginning, or when the project involves high levels of complexity or uncertainty. This makes it challenging to accurately estimate costs.

Another important contract to know is the Percentage of Construction Cost contract. In a Percentage of Construction Cost contract, the your fee is based on a percentage of the total cost of the construction of the project. This percentage will be agreed upon beforehand and is often used in your projects where the total construction cost could vary or isn't known at the very beginning.

Its advantages include flexibility and scalability; the architect's fee will adjust in line with the final cost of the project, keeping it proportionate.

The Construction Cost contract works the best for projects where the scope might change significantly, or the level of uncertainty is high, which as you know makes it hard to define a fixed cost.

Next we have the Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) contract. This contract is a more modern approach to contractual agreements. It really aims to bring together all stakeholders - architects, contractors, subcontractors, and owners - under one contract.

The goal of this contract is to foster a collaborative environment that encourages shared goals and success metrics before hitting the project site. By doing so, it promotes collective decision-making, shared risk and reward, and improved project outcomes through efficient and effective use of all participants' skills and insights.

The advantage of an IPD contract is that it can lead to innovative solutions, cost savings, and increased satisfaction due to the collective 'one-team' approach.

An IPD contract is particularly well-suited for complex or large-scale projects where collaboration, efficiency, and innovation are critical for success. It's an ideal choice when the project involves numerous stakeholders, all with significant contributions to the project's outcome. It’s also beneficial when the owner wishes to actively participate in the project's design and construction process.

A Design and Build contract is a project delivery system where the design and construction services are contracted by a single entity known as the design-builder or design-build contractor.

The design-build approach also allows for a high degree of project delivery speed, as design and construction of the project can happen simultaneously, reducing the overall timeline. It is advantageous in situations where fast project delivery is crucial, and there's a high degree of trust in the design-build contractor to deliver quality results.

This contract type is often preferred when a client wishes to deal with a single point of responsibility in a contracted arrangement, streamlining the process and fostering clearer communication.

The Design Bid Build contract represents the traditional method for project delivery, where your project is broken down into two stages: design and construction.

Now the design phase involves an architect or designer who works closely with the client to finalize the design. When the design is completed, the project is then put out to bid for contractors to execute the build.

A key advantage if you're going to use this contract is that it allows for a competitive bidding process for the construction phase, potentially leading to cost savings. The separation of design and construction can even provide your client with greater control over the project's design.

This contract is often used in situations where your client wishes to keep the design and construction phases distinct, or when the project's scope, scale, renovations, reproductions, and outcome need to be more closely controlled.

As you know from experience, oftentimes the most successful projects happen because of a clear and well-defined architect-client relationship. If you want this for every project, you'll need to create a comprehensive architectural contract that includes the right terms. Your contract should assign the roles, responsibilities, and expectations of both parties, to ensure that each party is on the same page.

A contract also serves to protect the interests of both your firm and your client. It outlines the scope of work, payment terms, intellectual property rights, dispute resolution mechanisms, and other key elements, so that both parties are protected from potential miscommunications or even costly disputes.

A strong architect contract can also provide legal remedies if one party fails to meet their obligations.

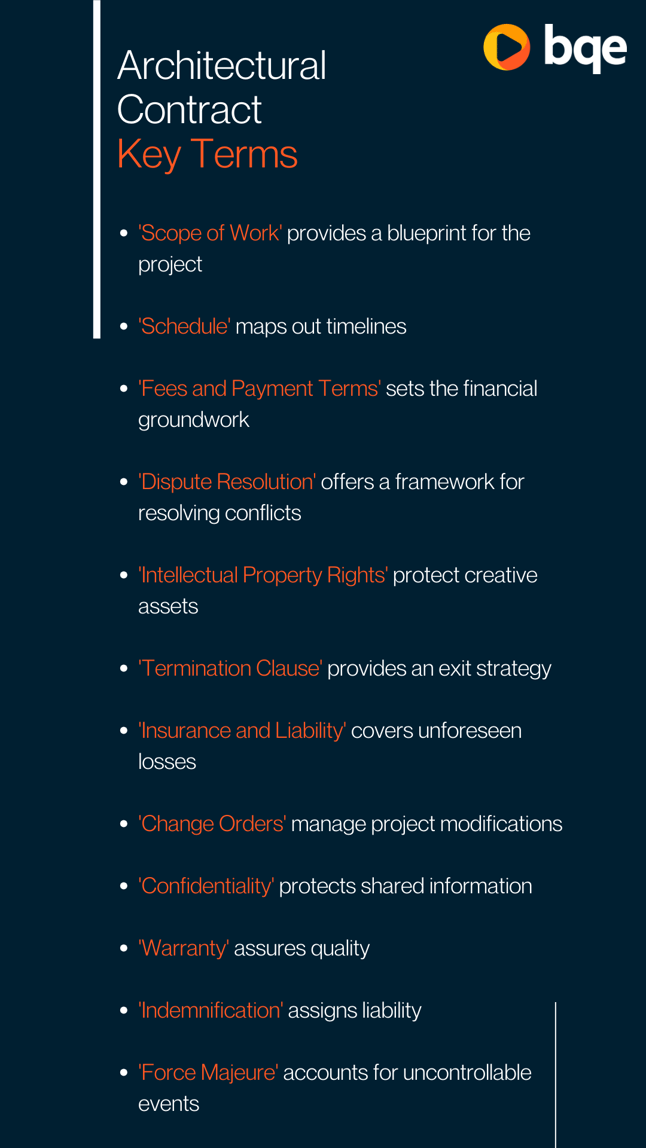

To help you create a strong architectural contract, the following terms should be clearly defined in the contract documents to ensure both parties understand their rights and responsibilities and scope of services.

The ‘Scope of Work’ outlines your responsibilities and the services you'll render throughout your project.

It outlines exactly what your client can expect from you and plays an important role in setting clear expectations. A well-defined scope can prevent scope creep and serve as a reference point in case of any disputes.

Now the 'Scope of Work' needs to be as precise as possible, detailing the various project phases, from the very first design and concept development, to your design execution, construction documentation, site supervision, and even post-construction services like project handover or follow-ups.

This is a very important part of your contract, so make sure you get it as detailed as possible.

The 'Scope of Work' specifics can vary of course based on the type of project and the size of your architectural firm. For instance, if you're a smaller firm, you may not have the capacity to offer extensive post-construction services, however if you're a larger firm this could be something you can do. Also, a simple residential project might require less detail in the scope compared to a complex, multi-use commercial development that uses more designs.

It's important to customize the 'Scope of Work' in the contract documents to align with your firm's capabilities, the project's requirements, and even your client's expectations. Any changes in your project's scale should be added in an updated 'Scope of Work'. This ensures it remains an accurate guide throughout your project's life cycle.

You should think of the 'Schedule' in an architectural contract as your project's timeline, mapping out when specific milestones should be met and marking the path to the final completion date. This such an important part of the contract for project management because it ensures that everyone involved has a clear understanding of the project's pace and timing. You know how frustrating it can be when you have a client constantly coming to you and asking when the project is going to get to a certain stage. Well, with a well written schedule, they won't have to!

Again, it all depends on the size of your firm and your project on the level of detail you need to include.

For a smaller project or if you're a smaller firm with less capacity, a high-level schedule with key milestones might work fine. However, for larger, more complex projects or if you're a larger firm managing multiple projects at the same time, a more detailed schedule that includes intermediate milestones, review times, buffer periods for potential delays, and clear deadlines for decision-making may be beneficial.

It's important that you customize the schedule according to your project's specific requirements and your firm's capacity. For example, if you're working on a residential project with a straightforward design it might set a shorter timeline than if you're working on a complex, large-scale commercial project. The schedule must account for elements beyond your control, such as permitting or client decision-making time. So it's a good idea to include regular updates to keep your schedule effective throughout the entire project.

‘Fees and Payment Terms’ is important because it lays out how you'll be compensated for your services in the final payment. It encompasses the fee structure, payment schedule, and terms for any additional services. A strong 'Fees and Payment Terms' clause provides clarity, aids in budgeting and financial planning for you and your client, discusses the possibility of additional cost, and helps prevent disputes down the line.

Whether you use a fixed fee, an hourly rate, a percentage of the construction costs, or a hybrid approach depends on the nature of your project as well as your preferred business model.

If you're a smaller firm or are working on a project with a tightly defined scope, you might prefer a fixed fee, providing predictability for both you and your client. However, an hourly rate or percentage of construction costs can be more appropriate for larger projects or if you're a larger firm. This is because the work's scope might be more fluid or the project's duration more extended.

Customizing the payment terms based on the project's specifics and the firm's financial needs is also crucial. It could include progress payments, milestone-based payments, or regular intervals like monthly or quarterly. The terms for additional services should clearly define what constitutes an extra service and how it will be billed.

The 'Dispute Resolution' is a good framework for resolving potential disagreements or conflicts that might come up during your project. By specifying preferred methods of resolution, such as negotiation, mediation, arbitration, or litigation, this term aims to provide a fair process to handle disputes. This is why it's such an important part of your contract.

Your choice of dispute resolution method often depends on the scale of the project and the nature of the potential disputes. For smaller firms or projects with less complex scopes, a simple negotiation process may suffice. Here, the parties involved can directly discuss and attempt to resolve issues. However, for larger firms or more complex projects, more formal methods like mediation or arbitration can be beneficial. These methods involve a neutral third party who assists in reaching a resolution.

Regardless of the method chosen, customization of the dispute resolution clause is essential. The process needs to align with the firm's capabilities, the project's specifics, and the preferences of both parties. The clause should clearly define the process, from initial notification of the issue through to the final steps of resolution.

These rights refer to the ownership and rights related to the designs, drawings, plans, and other intellectual outputs produced during the course of your project.

This is a very important part in the contract since it protects your creative rights and defines the extent to which your client can use the designs.

In some cases, you may retain full ownership of your designs, granting your client a license to use them for the specific project. This is common if you happen to be a larger firm or work on more unique, creative projects where the designs are a significant part of your portfolio and brand.

Now if you're a smaller firms or are working on more standard projects, the contract may transfer full ownership rights to your client upon payment. This can simplify the process and provide your client with more freedom in your project's future use, but it does mean you lose control over your designs. So it's something to think about carefully.

The 'Termination Clause' is pretty self-explanatory. It's a contract that outlines the conditions under which either you or your client can bring the professional relationship to an end. It's an important safety valve for both of you, providing a clear and agreed-upon exit strategy should the project encounter too many challenges, or should the relationship between you both break down.

If you're working with smaller projects or are a smaller firm, termination might be allowed for any reason, provided adequate notice is given.

In larger projects or firms, termination clauses may be more detailed, specifying allowable reasons for termination such as non-payment or breach of contract.

‘Insurance Liability’ refers to the different types and even the different amounts of insurance that you must have. It also defines how issues related to liability will be handled. This term serves as a safety net, protecting both you and your client from potential financial losses due to any mistakes that can pop up along the way.

Again, this all depends on your type of firm and project. Let's run through a couple of examples. As a smaller firm working on a residential project, you might only need basic professional liability (also known as 'errors and omissions') insurance. Yet as a larger firm taking on a high-profile commercial project you might also consider adding additional coverage types, like general liability, workers' compensation, or property insurance.

Liability clauses in architectural contracts also need to be adapted to your project's specifics. They should clearly define the extent of your responsibility for different types of potential issues, like design errors, delays, or budget overruns. For example, you might be held liable for design errors but not for delays caused by the contractor or unforeseen site conditions.

‘Change Orders’ refers to the agreed on process for implementing changes to your project. This is after the contract has been signed. As you're probably aware, change is almost inevitable, whether due to shifting client needs, unforeseen site conditions, changes in applicable laws or regulations, or other factors. Change happens and we often can't prevent it. But, we can protect ourselves from any issues that happen as a result! That's where change orders comes in.

Of course, the way you write a change order is always going to depend on the size or your firm and the project you're working on. If you're a smaller firm, or you're working on an average to smaller size project, your change order might be more on the informal side, consisting of agreed-upon adjustments to the project's scope, schedule, and/or budget. Now if you're a larger firm or even working on more complex projects, your change order process is probably going to need to be more formal and structured. This often requires detailed documentation, approval processes, and adjustments to fees and schedules. These are just some examples of what you might change, again, depending on size.

If you have a really well-written 'Change Orders' clause in your contract, it should outline how potential changes will be identified, who can initiate a change, how changes will be documented and approved, and how they will impact your project's cost and timeline. Ideally you should also specify any limitations or conditions on changes, such as deadlines for requesting changes or restrictions on the types of changes that can be made.

Now ‘Confidentiality’ is an important clause that you want to include because it restricts both you and your client from disclosing confidential or proprietary information shared during the course of your project. It really exists to help build trust between everyone involved and can be important in protecting competitive advantage, privacy, and other key interests.

Again, same as with the others, the size of your firm and project will effect how this is set up. If you're a large firm working on a high-profile project, your confidentiality clause might be particularly tight, with severe penalties for breaches and provisions to protect trade secrets or unique design concepts. However, if you're a small firm working on a more straightforward residential project, your confidentiality clause might be more focused on protecting your client's personal information and project details.

Now let's move on to the 'Warranty' clause. ‘Warranty’ is pretty much what you think it means. Just like when you have a warranty on your car or another expensive purchase. This one often refers to the promise that your services will meet certain standards of quality and performance. It provides assurance to your client you'll deliver services in line with agreed-upon professional standards, including adherence to specific design criteria, applicable laws and regulations, and reasonable skill and care in performing the work.

If you're a much bigger firm working on a complex, high-risk project, you might provide a more extensive warranty, perhaps including assurances about specific design features, the feasibility of the design for construction, or certain performance characteristics of the completed building.

If you're a smaller firm or you're working on a simpler project you might have a more basic warranty clause, perhaps focused mainly on compliance with applicable laws and regulations and general professional standards.

It's important that the warranty clause in your contract is crystal clear, realistic, and aligned with your capabilities and your project's needs.

Next we have 'Indemnification.' This refers to a party's obligation to compensate the other for certain specified damages or losses that they might incur. This is typically used to manage risk and ensure that everyone takes responsibility for their own actions. This provides a level of protection and reassurance for all those involved in the project. That's why it's a must-have when it comes to creating your contract.

Now say you're a large firm working on a major commercial project, you might agree to a broad indemnification clause, because it takes care of a wide range of potential damages and liabilities. This is because of the higher stakes involved. Yet, if you're a smaller firm working on a modest residential project, you might negotiate a more narrowly defined indemnification clause, focusing on clearly identified, specific risks.

The indemnification clause should be clearly worded to specify what kinds of damages or losses are covered, under what circumstances the indemnification applies, and the process for claiming it.

The term ‘Force Majeure’ relates to events beyond the control of those involved that may prevent the fulfillment of the contract obligations. These events can include natural disasters, wars, pandemics, or other 'acts of God' that could not have been anticipated or stopped.

If you're a bigger firm working on international projects, you probably want to prepare for a wider range of potential events such as changes in foreign laws. But if you're a small firm working on local residential projects, you probably want to focus more on events like local natural disasters.

Either way, a well-written 'Force Majeure' clause should clearly define what a force majeure event is, how it affects obligations, and the process for notifying the other party and working around the effects of the event. Some of these may include provisions for extensions of time, compensation, suspension or termination of the contract, among others.

To wrap up, a bulletproof architectural contract should include necessary key terms, each serving an important role in setting expectations guiding the professional relationship between you and your client.

When creating your contract, keep in mind how the above terms should form a strong outline so that you have every piece of a powerful contract in place.

Each term must be customized to align with your project's specific requirements, your firm's capabilities, and your client's expectations. With this tailored approach, your architectural contract becomes a powerful tool, ready to strengthen the architect-client relationship against potential pitfalls.

Now that you know how to craft a bulletproof architectural contract, it’s time to move on to creating a proposal. The proposal is a critical part of the client onboarding process. While there are multiple types of proposals, there is never just one that works for every project.

In BQE Software’s webinar, “Building a Better Proposal: How to Get Clients to Say Yes”, you learn what is included in the proposal, the difference between a proposal and an architectural contract, and the terms you need to turn that proposal into a contract.

BQE University is a hub of brilliant thought leaders in the architecture, engineering, and professional services industry. Each article offers a unique approach to education that emphasizes the importance of developing a business-thinking mindset for your firm. Their valuable knowledge and insights helps transform your business from a mere service provider to a thriving organization that consistently delivers projects that satisfy clients and generate profits. By learning from the experts at BQE, you can build a better firm and achieve your professional goals.

The engineering contract is the foundation of every successful project. Learn about the types of contracts along with the pros and cons of each.

Failing to meet DCAA timekeeping requirements can result in refusal of future contracts, delayed payment, fines and even jail time.

Navigating the DCAA Audit Manual can be tricky. Enlisting the help of DCAA compliant software can help simplify your job as a government contractor.

Be the first to know the latest insights from experts in your industry to help you master project management and deliver projects that yield delighted clients and predictable profits.